By focusing on hidden stories, you can share the cultural, historical, and environmental richness of a destination that might not be covered by mainstream tourist narratives.

This year on Canada Day, July 1st, the new Chinese Canadian Museum in Vancouver’s Chinatown neighborhood opened. The day was important because it was on July 1st 100 years earlier back in 1923 when Canada’s Chinese Exclusion Act came into effect and barred most immigration from China until 1947. The Legislative Assembly of British Columbia tells that in 1923, the Government of Canada revoked the head tax on Chinese immigrants, a large fee charged to Chinese people entering Canada, and replaced it with the Chinese Immigration Act. This virtually halted all immigration from China. Over the next 24 years, only 44 Chinese migrants entered the country. The restrictive immigration law and its human impact is featured in the museum’s opening exhibition titled “The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act.”

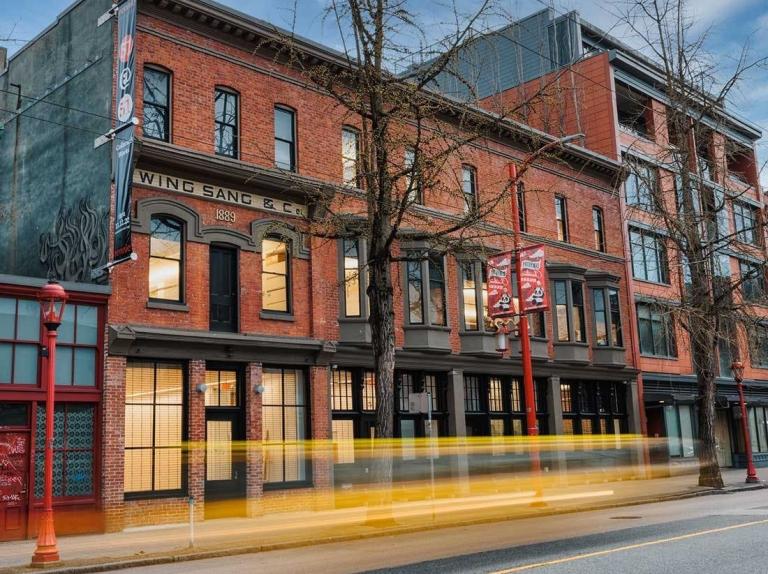

The Chinese Canadian Museum is now permanently at home inside the Wing Sang Building. Originally a two-storey structure built in 1889 by merchant Yip Sang, the Wing Sang Building was later expanded in 1901 and 1912 and remains the oldest building in Vancouver’s Chinatown. The heritage site was built in 1889 by pioneering Chinese Canadian merchant Yip Sang, who became an influential business leader. Vancouver real estate marketer Bob Rennie bought it in 2004 and restored it as an office and art gallery space. The building boasts 40-foot-high ceilings and spans 21,000 square feet. It is nearly twenty times larger than the temporary space next door.

Along with gallery exhibitions, the Chinese Canadian Museum will feature a period school room where Sang’s 23 children were educated, along with other students from the community. A blackboard still has writing in chalk from the 1960s. The top floor will also showcase a period living room with antique objects that re-create the 1930s, when Sang’s children and grandchildren lived in Chinatown. Outdoor films will be screened on a rooftop lawn that commands views of buildings built more than a century ago.

More than anything, the new museum spotlights hidden histories. The museum aims to help visitors understand how Chinese Canadians, “along with many other immigrants from around the world, have helped build and transform Canada” into a diverse and multicultural society, said Vivienne Poy, the country’s first Chinese Canadian senator.

Storytelling is at the heart of any successful marketing and promotion strategy, and this is especially true in tourism. Tourism, at its core, is about experiences, encounters, and the narratives we weave from these moments. Hidden stories and fresh perspectives have a special significance in this context for several reasons.

By focusing on hidden stories, you can share the cultural, historical, and environmental richness of a destination that might not be covered by mainstream tourist narratives. This not only promotes cultural understanding but also supports the local community by highlighting their unique histories and traditions.

Humans are inherently drawn to the novel and the unknown. Telling lesser-known stories or showing a well-known destination from a different perspective can evoke curiosity and interest in potential tourists, thereby attracting them to the location. When tourists learn about the unique, lesser-known aspects of a destination, their travel experience becomes more enriching and personalized. This can lead to higher satisfaction levels, increased word-of-mouth promotion, and repeat visits.

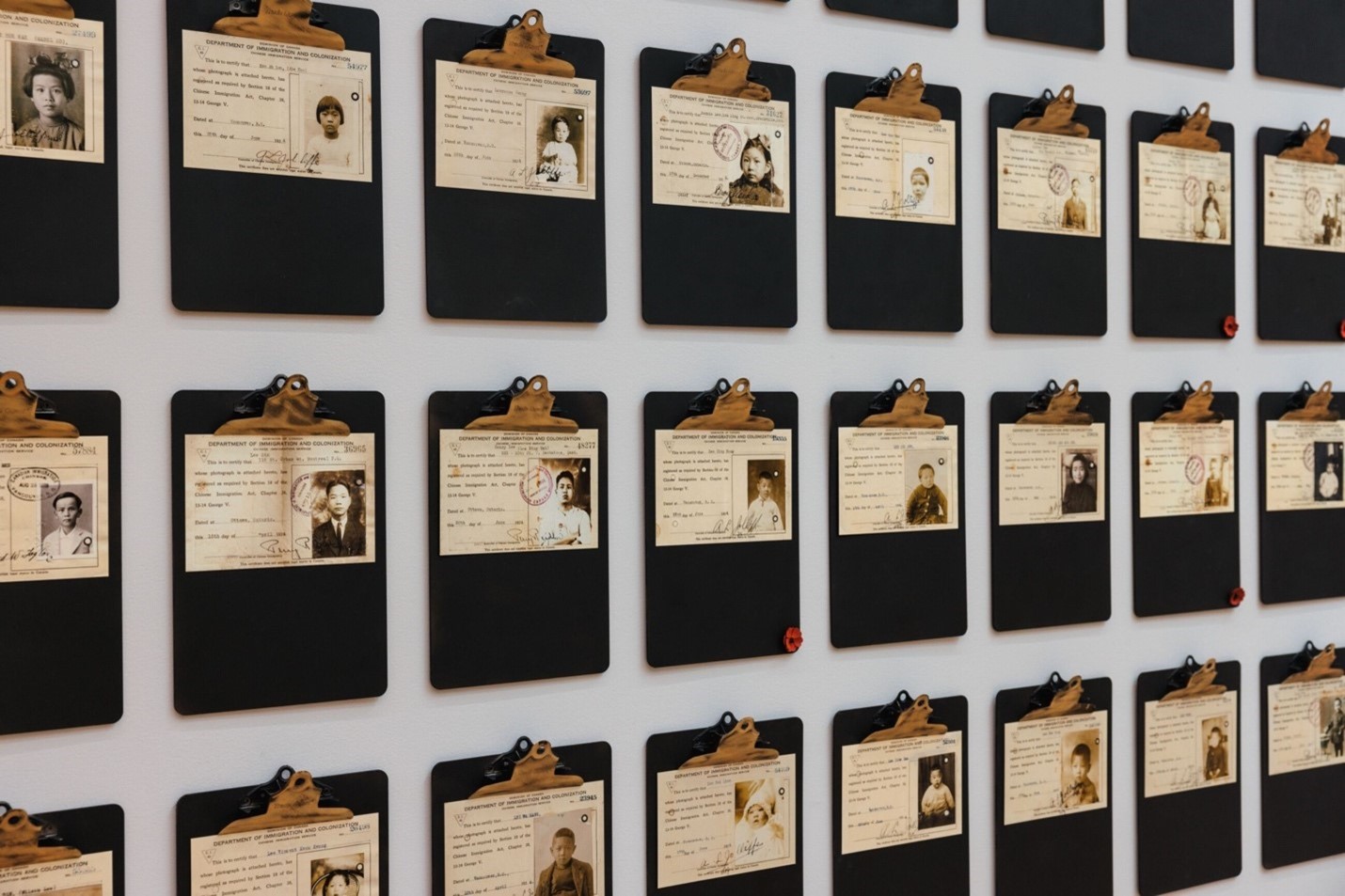

In the case of the Chinese Canadian Museum, the inaugural exhibition tells the lesser-known story of “The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act.” It shines a spotlight on early Chinese migrants, the faces of those who came to Canada in the 1800s to work in gold mines, build railroads and toil in other arduous jobs were captured in “certificates of identity” required only for Chinese people. These government-issued documents for Chinese migrants “were intended to control, contain, monitor and even intimidate this one community,” wrote curators of the exhibition. The documents were a “constant reminder of a second-class status in Canada.” More than 15,000 Chinese came to Canada to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. They were paid half as much as white workers and tasked with the most dangerous work, such as handling explosives, according to the British Columbia government.

A focus on hidden stories can also be part of your sustainability plan. By highlighting off-the-beaten-path stories and locations, tourism demand can be dispersed more evenly, helping to avoid over-tourism in hotspots and promoting a more sustainable and responsible form of tourism. This is the case of the Chinese Canadian Museum.

The Museum’s launch comes at a time when advocates are trying to save one of Canada’s oldest Asian enclaves from decay. Community leaders hope cultural anchors like the museum will bring visitors back to Vancouver Chinatown and help revitalize local shops and restaurants in the historic neighborhood. It joins other nearby tourist attractions such as the Dr. Sun Yat Sen Classical Chinese Garden and the Chinatown Storytelling Centre, which opened in 2021, mid-pandemic.

“This is Canada's first and only public museum dedicated to Chinese Canadian stories,” said Royce Chwin, President & CEO, Destination Vancouver. “The stories of the first Chinese immigrants and of Chinatown are so inextricably tied to the history and development of Vancouver, and of our province, that it’s astonishing it has taken so long to give this rich, and often painful, chronicle the attention that it so thoroughly warrants.”

Royce Chwin also said that “Vancouver’s Chinatown is one of the largest, most vibrant, and historic Chinatowns in North America and has always been a draw for visitors. But the area has fallen on difficult times. Tourism is an important contributor to the economic sustainability of the neighborhood and to its cultural attractions. At Destination Vancouver, we want to see Chinatown, not just survive, but to thrive and overcome the recent challenges that the neighborhood has experienced.”

It also is a competitive advantage. Every destination has its own unique story to tell, and by telling these hidden stories and alternative perspectives, you can differentiate your destination from others. It helps create a unique selling proposition in the highly competitive tourism market.

Finally, finding and telling those hidden stories is part of a greater effort to preserve your community’s heritage. Many hidden stories are tied to important historical, cultural, or natural heritage. By bringing them into the light, you help raise awareness and potentially mobilize resources for their preservation.

This was the case for the inaugural exhibit in Canada. Many identity documents were lost or destroyed over the years. Surviving ones were stowed away and forgotten. But three years ago, a research team asked Chinese Canadian families to contribute certificates for the exhibition. Those photos and accompanying stories are featured on some 140 wall-mounted clipboards that can be perused individually.

Certificates bearing faces and names such as “Charlie Chow C.I.36 Moose Jaw, SK” and “Kwan Kwai C.I.30 Vancouver, B.C.” are now memorialized for posterity. About 400 scans of CI documents were collected and will be housed in a public online archive at the University of British Columbia. “Through these aging, fragile pieces of paper we can learn the story of the individual who owned it; the struggles of an early immigrant community; and the story of a dark period in Canadian history,” wrote the curators on their website.

To successfully tell hidden stories and promote different perspectives, tourism leaders need to work closely with local communities, historians, cultural institutions, and other stakeholders. Authenticity is key: the story must be true, compelling, and respectful of the local context. By doing this, we can create a more inclusive, engaging, and sustainable form of tourism. The new museum in Vancouver spotlights the contributions and hardships of Chinese immigrants who were once relegated to shadows. “We tell stories that are hidden, and from a different perspective,” said Melissa Karmen Lee, chief executive officer of the Chinese Canadian Museum. “It’s the life’s work of museums to tell these stories.”

Uncovering hidden stories requires a mix of research, community engagement, and creative thinking. If I were still working for a destination organization, here's some of the things I might do to go about finding these stories. Many of these would hopefully be a regular part of a community engagement, collaboration, and inclusion strategy as part of my destination organization efforts to be resident focused and seen and valued by the community. All part of being a community shared value and following our community alignment roadmap.

- Engage with Local Communities: The best source of unique, lesser-known stories often comes directly from local communities. Regular meetings, workshops, and informal chats with residents can yield a wealth of information about the area's history, culture, and unique aspects. Engage with people from various backgrounds and age groups to get a diverse array of narratives.

- Collaborate with Local Historians, Cultural Institutions, and Elders: Local historians, museums, cultural institutions, and community elders often hold a treasure trove of stories that are overlooked or underrepresented. These sources can provide insights into historical events, cultural traditions, or other unique aspects of the local community that might not be widely known.

- Research Local Literature, Art, and Media: Books, films, paintings, music, and local newspapers can provide insights into a destination's culture and history. These sources can also reflect local voices and perspectives, which can lead to interesting stories or angles.

- Explore the Landscape: Spending time exploring the local area—its natural features, buildings, monuments, and landmarks—can also lead to hidden stories. For example, a peculiar building might have a fascinating architectural history, or a seemingly ordinary park might have been a significant site for a historical event.

- Partner with Schools and Universities: Educational institutions often conduct projects or research that delves into local history or culture. They can provide academic insight into interesting aspects of the area that may not be well-known.

- Crowdsourcing: Use social media or digital platforms to invite residents and visitors to share their unique stories or experiences about the destination. This method can yield surprising and authentic narratives that can be curated and shared widely.

- Participate in Local Events: Attending local festivals, markets, and community events can provide a deep understanding of local traditions, customs, and the community’s way of life, uncovering unique stories along the way.

Remember, the process of uncovering hidden stories should be respectful and sensitive to the community's feelings and wishes. Not all stories might be appropriate for sharing widely, and the community's wishes should be honored in these instances. Furthermore, it's important to present the stories accurately and authentically, maintaining the essence of the narrative and the dignity of the people involved.

Building a strong connection with the community through the telling of stories that are hidden, and telling them from a different perspective, a destination organization can build a strong connection with the local community that not only benefits the organization and the community but also enriches the experience for visitors.