by: Jack Johnson, Destinations International

Elections are often viewed as a win or lose situation, up or down, yes or no. And for individual candidates, they often are. Elections are a time of great triumph or stinging defeat. For some of those who were defeated, there is often the attempt to salvage a victory, albeit a moral one. They often fall into the categories of “we did better than expected” or “we broke barriers and took the movement forward” or “we raised issues that were not being addressed” or “we forced them to answer questions and be accountable.”

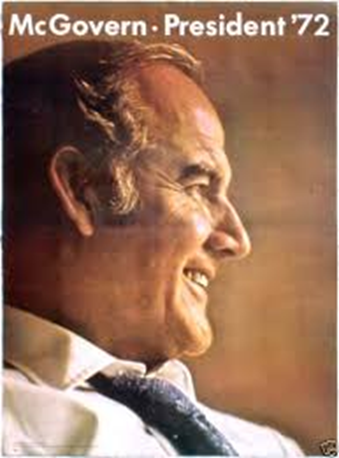

My sentimental favorite is the way George McGovern tried to position his landslide loss to Richard Nixon in his 1972 concession speech.

“I want every single one of you to remember and never forget it that if we pushed the day of peace just one day closer, then every minute and every hour‐and every bone crushing effort in this campaign was worth the entire effort. And if we have brought into the political process those who never before have experienced either its joy or its sorrow, then that, too, is an enduring blessing.

Now, the question is to what standards does the loyal opposition now rally? We do not rally to the support of policies that we deplore. But we do love this country and we will continue to beckon it to a higher standard.

So, I ask all of you tonight to stand with your convictions. I ask you not to despair of the political, process of this country, because that process has yielded too much valuable improvement in these past two years. The Democratic party will be a better party because of the reforms that we have carried out. The nation will be better because we never once gave up the long battle to renew its oldest ideals and to redirect its current energies along more humane and hopeful paths.”

It was the first national election I had paid attention to and I remember being impressed by how thoughtful his speech was. It was clearly not a speech thrown together at the last minute by someone expecting a win and then being surprised with a loss.

I think that speech was what led me in later years to pull my candidates aside several months before an election and talk about what they wanted to accomplish other than just winning. And then writing a draft of a concession speech to file for election night if it was required. For the record, I don’t want to over-sentimentalize that moment - we would also talk about the skeletons in their closet that might leak out so we could also write those press releases in advance. Then there was the conversation of how much they were willing to do to win – what lines could or could not be crossed.

Moral victories should be noted and, as I have pointed out, can offer wonderful moments (too often unused!) for inspiring oratory. But in the end, they are just a subcategory of loss and, despite the name, not a win.

It was a few years after that 1972 election that I realized that power brokers, political parties and perhaps even “movements,” entered the field of electoral battle with the understanding that there were three possible results, not just two. There are the two obvious results - the best outcome and the worst outcome; win or lose. But there was also something in between. It might be described as a status quo result though it is usually closer to something like a “we can work with that” outcome.

The first time I noticed the third result was in 1976 while living in Chicago, Illinois. Four years earlier in 1972, an insurgent populist named Dan Walker pulled an upset in the Democratic Party primary and went on to win the general election. For the next four years, he was a thorn in the side of the regular Democratic Party organization led by then Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley. For four years, the two waged war over just about everything.

Come 1976, Mayor Daley made it his number one mission to defeat Governor Walker and slated a long-serving state official, Secretary of State Michael Howlett who had won several statewide elections, to run for the Democratic nomination for Governor. Howlett had not wanted to run for governor, wishing instead to finish out his career as Secretary of State. But Daley insisted. Walker successfully labeled Howlett as a tool of Mayor Daley and the famous or infamous (depending on your point of view) Chicago Democratic “machine” and unfortunately Howlett just looked like an old political hack (he was anything but that). In an ugly campaign, Howlett, with the power of the Cook County Regular Democratic Organization behind him and the personal support from dozens of years in state politics, was able to best Walker in a rather close primary and went on to the general election. But by then he was damaged goods and Republican Jim Thompson easily carried the day.

What had surprised me was that while the Democrats poured everything they had into that primary to win, they did not do the same in the general election. Sensing a Republican victory, halfway through the race they moved their resources elsewhere. The Democratic organization had succeeded in avoiding the worst-case scenario – Walker winning. While it would have been nice for Howlett to win – the best option – negotiating with the Republicans was so much better than the worse option of Walker being reelected, that it was not only an acceptable option, but it was also an improvement in their situation. They could work with that.

Over the next several decades I would see that third option become the target over and over. If you cannot win, at least don’t end up with the worst option; find the third option – the one you can work with.

So, what does this have to do with the Canadian election? Certainly, when Justin Trudeau called for an election two years ahead of schedule he was hoping, planning even, to ride the party’s current approval over the handling of the COVID-19 Pandemic to victory and a Liberal Party majority. One can argue that he underestimated the possible backlash of calling an election during a pandemic, particularly since his ability to govern was not being impaired by his coalition partners.

You could also argue that Justin Trudeau forgot that calling an election as a reward for doing his job was not really a winning strategy. As Daniel Béland, a political science professor at Montreal’s McGill University, said “adequate pandemic management is no longer sufficient to win re-election in the post-Covid world.” It is also worth noting that Trudeau’s Liberals will be governing after receiving one of the lowest, if not the lowest, share for any governing party in the nation’s history. And, for the second straight election, Trudeau’s party trailed the Conservatives in the popular vote. So, it would be easy to say that Trudeau rolled the dice and lost. But did he? Applying the rule of three options suggests that while Trudeau did not win, he really did not lose either. Instead, it looks to me like he may have an outcome that he can work with – one that might be better than his pre-election situation.

A true loss would have been Conservative Leader Erin O'Toole convincing the electorate that the Conservative Party had moderated and, building off Trudeau’s missteps, deserved an opportunity to lead. In the end, that did not happen. While they maintained a plurality of the vote, they lost two seats.

O’Toole seemed to risk great personal capital in moving his party to the center and with nothing to show for it, he seems weakened. His position is further complicated by Maxime Bernier’s right-leaning, anti-mask and anti-lockdown People’s Party of Canada, who saw their vote share increase from 1.6% in 2019 to around 5% this time around, received enough of a vote to be a factor in what the Conservative Party does going forward. You can argue that the People’s Party cost the Conservative several seats, particularly in Ontario. Or not. Either way, it seems like O’Toole is in a weak position. It seems to me that if he moves right to get those votes he will most likely lose those he gained in the middle. If he continues to moderate to capture more votes in the center, he risks further erosion on the right.

Note: The Conservatives will hold their first post-election caucus meeting in Ottawa after this blog is published. At that meeting, Conservative MPs are expected to vote on whether to give themselves the power to potentially oust him.

With Ontario voters heading to the polls mid-way through 2022, it is worth noting that Premier Doug Ford, who remained neutral and forbade his caucus and staff from helping O’Toole’s Conservatives during the campaign, is more in line with Trudeau, at least on pandemic-related issues. Ford seemed to stake his ground in the political center, insisting his Conservatives “would not be undermined by right-wing fringe parties on pandemic policies.” That removes a potential roadblock for Trudeau in terms of pushing his pandemic-related policies into action. Given that in the 78 years since 1943, different parties have been in power federally and in Ontario for all but about eleven years, this is no small thing.

Finally, popular Alberta Conservative Party leader, Premier Jason Kenney's controversial response to the devastating fourth wave of COVID-19 most likely not only hurt O’Toole but also damaged Kenney. Nicknamed the "Kenney effect," the Conservative Party vote in Alberta fell by nearly 14% in the federal election given them a winning percentage of 55.4% of the vote, down from the 69% they received in 2019. That allowed the New Democratic Party (NDP) and the Liberals to gain a foothold in some ridings. Kenney’s electoral setback and personal loss of popularity suggests to me he has suffered a reduced ability to be a voice of opposition.

As for the other three major parties, the wind seems to be against them. The Canadian Green Party seem to be in process of imploding. The Greens saw their support drop to around 2.2% from 7% in 2019. Internal strife over policy positions not a priority with voters, the loss of dominance in the global warming issue and a leader that was unable to resolve either of those. The NDP was unable to regain most of the seats they lost in the 2019 election despite spending most of what they had in the bank. They ended up with 25 seats, just one more than they held before, and in fourth place behind the Bloc Québécois. The DNP are influential because they have the number of seats needed to form a majority with Trudeau (so does the Bloc Québécois) but they do not seem to be a threat. As for Bloc Québécois, from what I can tell, they seem to have strengthened their position with primarily French-speaking residents of Quebec while losing ground with the primarily English-speaking residents. Like the NDP, they have influence but they do not seem to be a threat.

All in all, it seems as if Trudeau’s position has improved. Not in the way of a sweeping majority and not necessarily by his strength. But, more so through the weakening of all his opponents. It seems to me that Trudeau and his Liberal Party did not lose; instead, they found a result they could work with.

On a final note, the last time a prime minister and political party put together a governing coalition after failing to win a majority in two consecutive elections - Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson and the Liberal Party - they ended up enacting Canada’s National Medical Care Insurance Act (passed in the House of Commons on December 8, 1966, by an overwhelming vote of 177 to 2). The Act provided that the federal government would pay about half of Medicare costs in any province with insurance plans that met the criteria of being universal, publicly administered, portable and comprehensive. By 1971, all provinces had established plans which met the criteria.

It seems Lester B. Pearson also found something he and the Liberal Party could work with.