By Jack Johnson, Destinations International

A few months back, I wrote about the funeral home around the corner from my house in Alexandria, Virginia USA and how they have become an almost daily reminder, sometimes twice a daily reminder, of the effect of the global pandemic. They still are.

I also pointed out that in a matter of months, there had been over 500,000 deaths worldwide. Most likely more. Over 125,000 deaths in the United States alone with another 8,500 just north in Canada. That number continues to grow.

Those of you who know me, even just casually, know that I cringe at the phrase “the new normal." As I have pointed out, there are many words that can be used to describe what we are living through. Crisis. Disaster. Catastrophe. Emergency. Calamity. Or just a huge predicament. Perhaps something more descriptive. Epidemic. Pandemic. Plague. Outbreak. Or one of my favorites, a massive virulent disease. But this moment in time is not normal.

This past week the U.S. passed 250,000 confirmed deaths from COVID-19. In Canada, it is well over 11,000. And across the world, the total will most likely pass 1.4 million this week. It probably crossed that threshold some time ago. These figures are truly vast – perhaps too vast for us to comprehend.

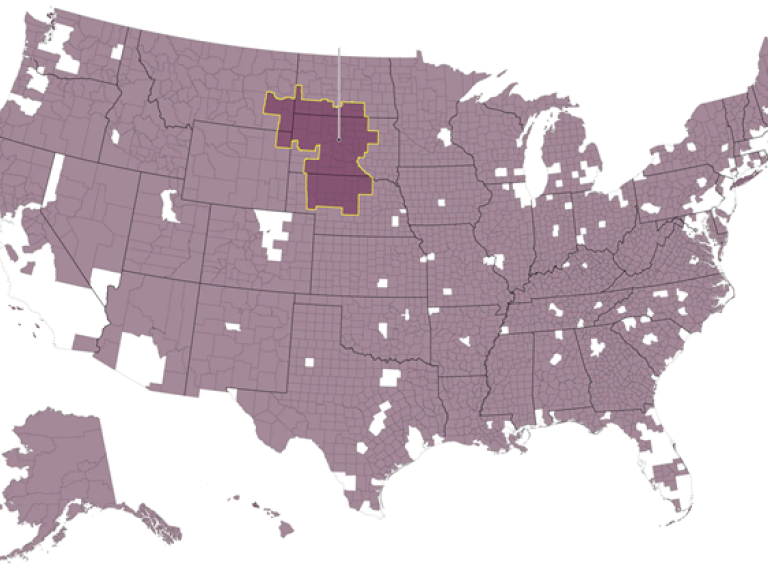

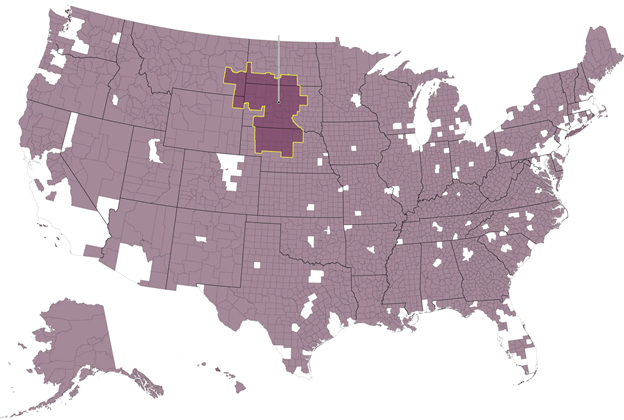

Experts tell us that the psychic numbing that sets in around mass death saps us of our empathy for victims and discourages us from making the sacrifices needed to control the situation. As to combat this, in the U.S. the media has tried to put the numbers in some kind of perspective. 250,000 deaths are ten times the number of American drivers and passengers who die in car crashes each year (CNN) or more than twice the number of American soldiers who died in World War I (NPR) or enough to draw a vast hole in America's heartland, if the deaths had all been concentrated in one area (Washington Post see below). These are interesting but do not quite do the trick.

According to Paul Slovic, a psychologist at the University of Oregon who studies human judgment and decision-making, even if we try our best to grasp mass death, we inevitably come up against our cognitive biases. Worse, as the scale of deaths and tragedy grows, our own compassion and concern fail to keep pace. As Slovic once simply put it, "the more who die, the less we care."

In any moral calculation, we should find 250,000 deaths much more horrifying than a smaller number. But in practice, we do not. It is as we had a set capacity for empathy and concern that tops out well below the scale of this pandemic. I have found myself in this quandary, a battle between what should be my rationale and moral response and what is my actual response.

Earlier this year, I watched the numbers climb daily toward 100,000 with a mixture of shock and dread and sadness. Today it is more like what I warned against a few months back. I wrote “The problem with using the word normal is that we change something that requires a response, something that requires sacrifice, something that requires a strategy to defeat, something that requires us to marshal our assets, something that requires vigilance, something that requires uniting, something that requires coordination, and something that requires action by every person in the world – no matter how remote they may be – and we change it into just another part of our day. Something we do not give much thought because it is normal.”

There are lots of reasons for this (see link at the end of this post). Studies show that we often react to the proportion of the situation while neglecting the scope of the raw number. We feel we can help and therefore, care if it is 100 out of 300 million. Not so much when it is 250,000 out of 300 million. These same cognitive biases make it difficult for us to fully appreciate many large chronic threats like climate change, or to prepare for rare but catastrophic risks in the future — like another pandemic. The sheer scope of these numbers makes the crisis feel more unreal, and for some, that much easier to deny altogether.

More, we live in a 24-hour news culture driven by the visual that focuses on specific, identifiable victims over mere numbers. Add this to the routine and habit that has set in after months and months of the pandemic, it shouldn't be surprising that most of us are becoming numb to the continued spread and devastation of COVID-19 now than when the number of sick and dead were far lower. And it does not help that for most of us those personal battles for life and all those deaths go unseen, hidden behind the walls of hospitals and nursing homes and funeral homes.

I plead guilty to this. Despite my best efforts, despite noting and often watching the funeral processions around the corner pass by, despite reviewing the numbers and news around the pandemic almost daily and maintaining my isolation efforts, I feel numbness and detachment. Or at least I did until last Friday. That was the day I learned that my older brother Michael had tested positive (FYI - The initial symptoms are currently mild, and we keep a close watch). To date, I have known people from my life who have had COVID and even died from it. But it has not, until now, reached into the tight circles of my close personal relationships.

All this makes me think that given our inherent cognitive biases, and the re-enforcement that they have received from most media practices, and the habits formed in a daily pandemic life, our best bet is to face this numbness directly, steer into it, lean into it, and daily remind ourselves that each of these cases, each one of these deaths tells an individual story. To paraphrase Holocaust survivor Abel Herzberg - there were not eleven million Jews, homosexuals, political prisoners, Romani, Slavs, disabled, mentally ill and others murdered; there was one murder, eleven million times."

As the toll of those who have been infected, those who have become sick and those who lost their lives continues to rise it will take a conscious effort by each one of us to appreciate what is happening. To understand that each individual number represents an individual person. And each individual person has family and friends who are individual people. This is not easy. It goes against our cognitive biases. But it is an effort that must be made every day. And if we do this, and we change the way we think, if we do this and change our biases, if we do this and empower our moral compass than those who have died will not have died in vain.

Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios

For more on why we are numb to 250,000 coronavirus deaths and further information on our cognitive biases, check out this article on Axios by Bryan Walsh, author of Future.